Submitting Chasing the Setting Sound (Float) and Melt 5

Melt 5

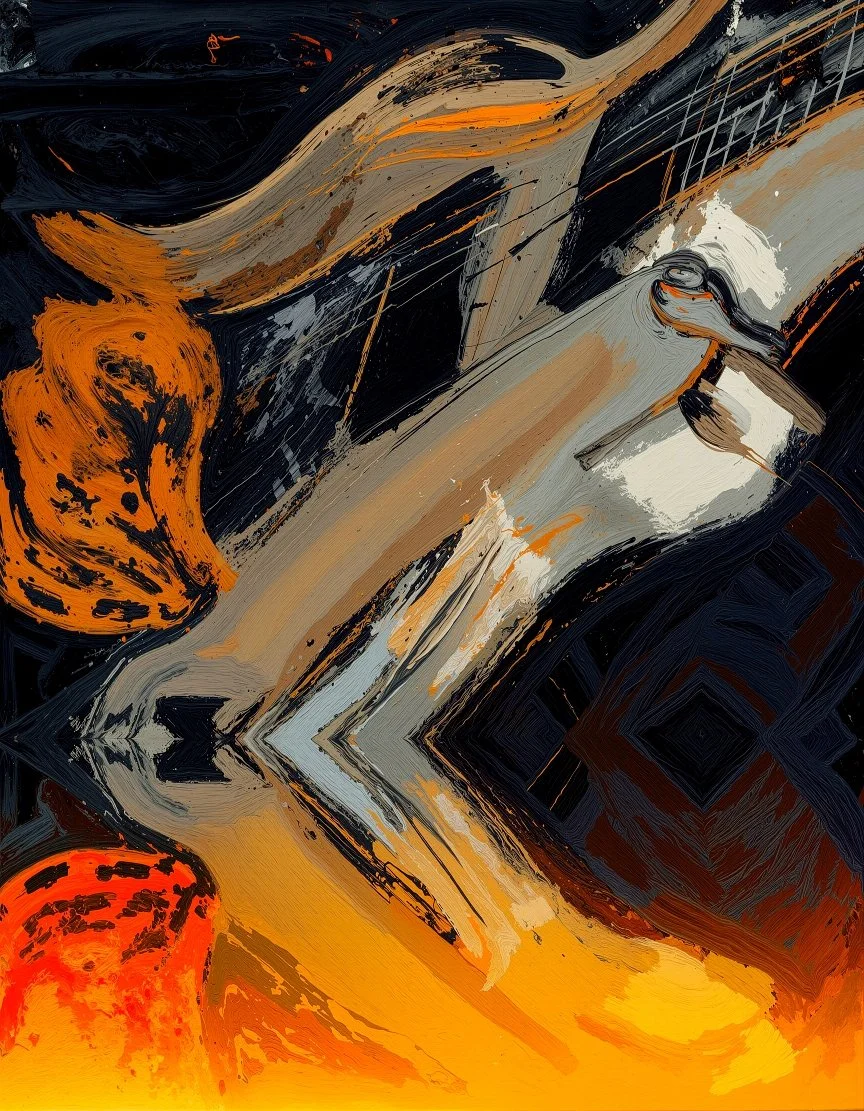

Chasing the Setting Sound (Float)

Lake Effect: Artists from Cleveland Now

I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about what it means to submit work to an institution—not just whether the work is “good enough,” but whether it is honest enough about where it comes from and where it’s going.

For the Cleveland Museum of Art’s Lake Effect: Artists from Cleveland Now, I chose to submit two works: Chasing the Setting Sound (Float) and Melt 5. They are not meant to summarize everything I make. Instead, they mark a through-line—a point of origin and a point of pressure—within the body of work I’ve been developing under the framework I call Without Square.

Chasing the Setting Sound (Float) is where that framework began. The piece originated from a practical problem rather than a theoretical one. I was thinking about how an image might exist on black without being boxed in by a printed square—how to let a form sit directly in space without containment. Removing the square wasn’t a stylistic move at first; it was a refusal. Once the frame disappeared, the image stopped needing to resolve itself. Edges softened. The guitar ceased behaving like an object and began to act more like a presence—floating, provisional, unfinished. That decision became foundational.

The title comes from music. Anyone who plays knows the feeling of chasing a sound that never quite settles. Visually, that idea carries through the work. The image resists grounding. It hovers between recognition and abstraction, between contact and release. What remains is not an instrument, but the sensation of sound just before it becomes fixed.

Melt 5 pushes that idea further. Where the earlier work floats through suspension, Float 5 floats through instability. It originates from the same photographic language, but the form is no longer allowed to hover gently. Instead, it is stretched, torqued, and compressed by opposing forces. There is no central anchor and no resolved edge. The image behaves like a field under stress—directional, charged, unresolved.

Together, these two works outline what Without Square has become for me. It is not just the absence of a frame. It’s a way of working that challenges visual enclosure at multiple levels: compositionally, materially, and conceptually. Cropping avoids symmetry. Space refuses to sit behind the subject. Even when the work exists within a rectangular format, it resists behaving like a contained object.

Submitting these pieces to Lake Effect feels appropriate not because they reference Cleveland directly, but because they come out of a Cleveland way of thinking—working with constraint, weather, friction, and persistence. This exhibition consciously recalls the spirit of the Cleveland Museum of Art’s historic May Show, a tradition that centered regional artists and the conditions they work within. Lake Effect isn’t about nostalgia; it’s about present tense. These works live firmly in that present.

Whether or not they are selected, the act of submitting them together matters. They represent a clear decision about what I’m producing now, what I’m refusing, and what I’m allowing to remain unresolved. The square is gone. What’s left is movement, pressure, and the space where something almost settles—but doesn’t.