A Moment in Time I Don’t Take Lightly

A Moment in time

I feel incredibly privileged and lucky to have the time, the health, and the financial stability that allow me to look inward, find the art in my soul, and let it breathe.

I don’t say that casually. Time, health, and stability are not givens. They are fragile, unevenly distributed, and easily lost. To have all three at once is not something I assume. It’s something I notice. It’s something I hold carefully.

Because of that, this moment carries responsibility.

I’m not making work to chase relevance or attention. I’m not trying to explain myself into existence. I’m listening for what asks to be made when the noise settles. Some days that arrives as music. Some days as an image. Sometimes it arrives as nothing at all — just the awareness that silence, too, is part of the work.

Lately, I’ve been moved by watching others step forward with their stories. Strangers, carrying years of living into a few vulnerable minutes. Their courage opens something in me. Not envy. Not comparison. Recognition. We respond because we see ourselves reflected back — our losses, our persistence, our unfinished hopes.

That exchange matters.

Art isn’t separate from life. It’s how life speaks when words fall short. It’s how one person’s honesty becomes another person’s permission. When we allow ourselves to feel a stranger’s truth, distance collapses. We remember what connects us.

So today, I’m choosing not to rush. Not to force meaning or conclusions. I’m letting the work arrive at its own pace. Letting the art breathe also means letting myself breathe — staying present with gratitude, with memory, with whatever this moment offers.

This is a moment in time I don’t take lightly. And for now, that awareness is enough.

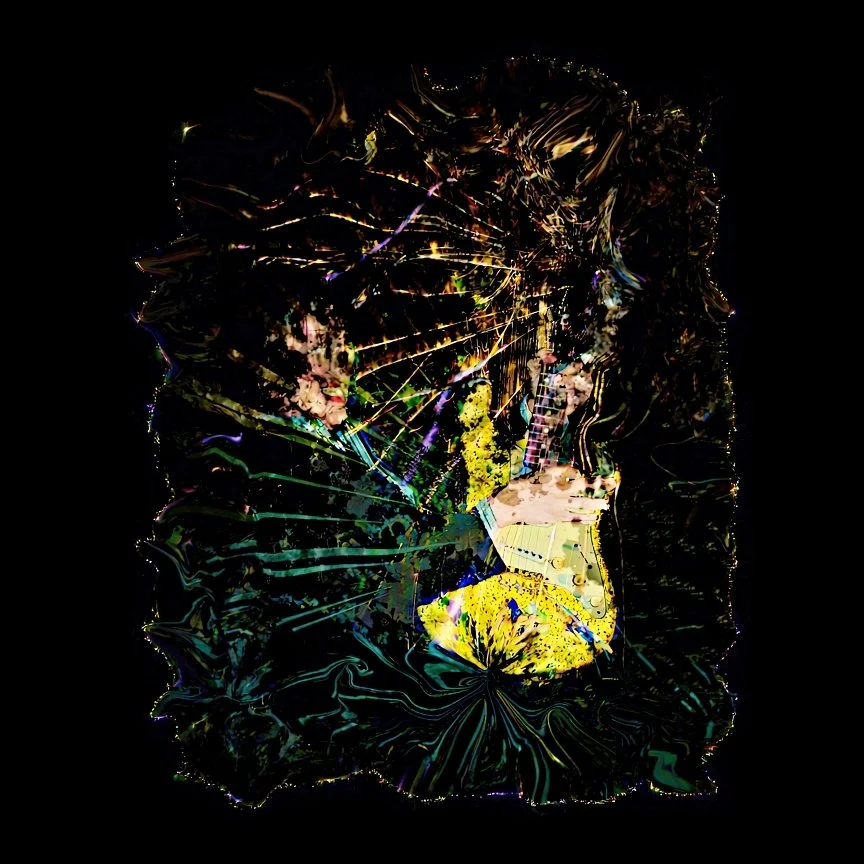

Bottleplay 3

Bottleplay 3

Bottleneck Slide

A photograph is a claim of permanence.

It says: this happened, and it will stay this way.

The original image does exactly that. A hand, a bottle, a moment fixed long enough to be trusted. The object knows what it is. The frame holds it in place. Nothing moves unless memory moves it later.

Bottleplay 3 begins there — and then refuses to stay.

Once brought into Without Square, the image lets go of its obligation to be still. The square no longer pins the moment down. The edges loosen. Gravity becomes optional. What was once fixed becomes suspended, not frozen but hovering — caught between states rather than locked into one.

This isn’t abstraction for its own sake. It’s a shift in time.

In the photograph, the bottle is permanent.

In Without Square, it becomes temporary again.

The hand no longer documents possession; it suggests motion. The object no longer rests inside a moment; it drifts through it. The image stops saying this was and starts asking what if it doesn’t stay.

You might still recognize where this came from. That recognition arrives quickly — and then dissolves. What replaces it is movement without destination. A form no longer anchored to use, brand, or outcome. A moment allowed to continue rather than conclude.

This is what Without Square changes.

It doesn’t destroy the photograph — it releases it.

I like the original image because it holds time still.

I like this version because it gives time back its motion.

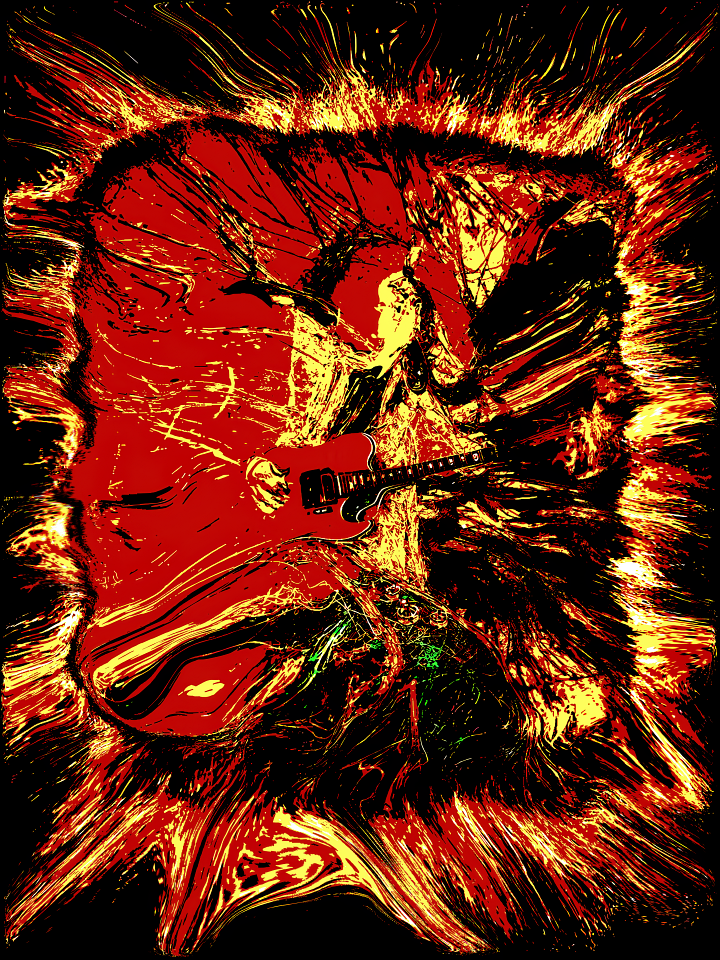

Matchbook 26 — Without Square

Matchbook 26

The world as we knew it is disappearing right in front of our eyes.

Not abruptly. Not all at once.

But steadily enough that it is becoming harder to believe what we see, and harder still to agree on what is real.

Climate change dominates headlines—even when it’s softened into phrases like “a one-in-a-hundred-year storm.” Masked, armed men aggressively threaten and hurt people of all kinds. AI is rapidly developing toward forms of intelligence that disrupt nearly everything—good and bad—that has been. The familiar world is still here, but it is barely visible now, like an afterimage.

Without Square began with that instability. It is not a rejection of form, but a rejection of the frame that once promised certainty. The square—long trusted as structure, balance, containment—can no longer be assumed. When the square disappears, the image must either hold itself together or reveal what happens when it cannot.

Matchbook 26 exists in that moment.

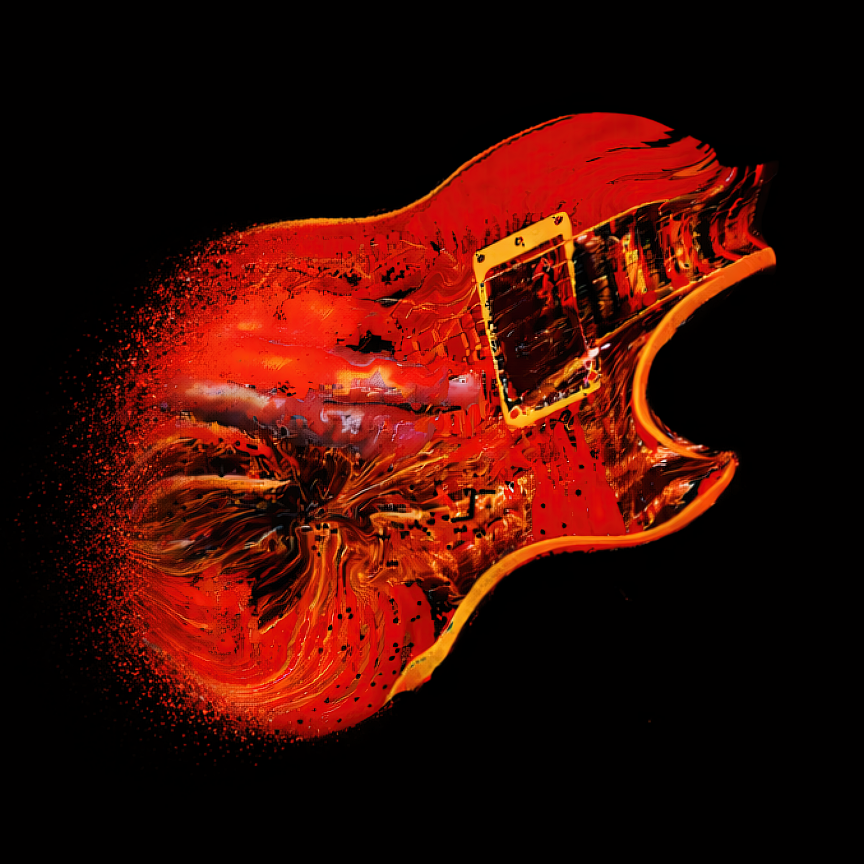

At first glance, there is something recognizable: a guitar, hands, the posture of playing. These are familiar anchors. But recognition doesn’t last. The longer the image is held, the more it refuses to stabilize. Edges dissolve. Light fractures. Motion begins to outweigh object.

This is not a depiction of a musician. It is a depiction of ignition.

The guitar behaves less like an instrument and more like a conductor—its strings extending outward as lines of force. What should be surface becomes heat. What should be form becomes release. The hands remain partially intact, but unstable, suspended between control and erosion. They suggest intention, but not mastery.

The boundary of the image burns irregularly. There is no clean border, no stable frame to step behind. Micro-sparks and filaments of light trace the perimeter as if the image itself is shedding energy into darkness. Containment has failed, but collapse has not yet arrived.

A match is inert until it isn’t.

For a long time it is only potential—paper, sulfur, waiting. Then pressure, friction, contact. In an instant it stops being matter and becomes energy. There is no middle state. One moment it is form; the next it is reaction.

Now imagine all the matches igniting at once.

A matchbook is designed for one flame at a time. When all the matches light in unison, the book burns fast. The object itself becomes irrelevant. What matters is the release.

That is the core image behind Matchbook 26: we try to hang on, but all we have left in our hand is an empty matchbook with a heavily burned edge.

2026 is that ignition moment—the matches going up in flames while we wonder what we will have in its place.

People are asking questions right now, whether they say them out loud or not:

What can still be trusted when familiar structures stop holding?

What remains real when clarity dissolves faster than understanding?

Are we watching destruction—or transformation that doesn’t yet have a familiar shape?

The image does not answer with slogans. It answers structurally. In Without Square, meaning does not arrive through resolution. It emerges through tension. Recognizable forms still exist, but they no longer stabilize the scene. Reality hasn’t vanished—it has become unstable, active, and difficult to pin down.

And yet fire is not only destruction.

Fire reveals.

Fire consumes what cannot endure.

Fire clears space.

So the final question—quietly present in the burn—is not whether something is ending. It is what will be left after the heat passes.

Will it burn away what is cruel and false?

Will it leave room for something more honest to grow?

I think it will.

I believe we can grow into a more pure form of love.

And I am watching.

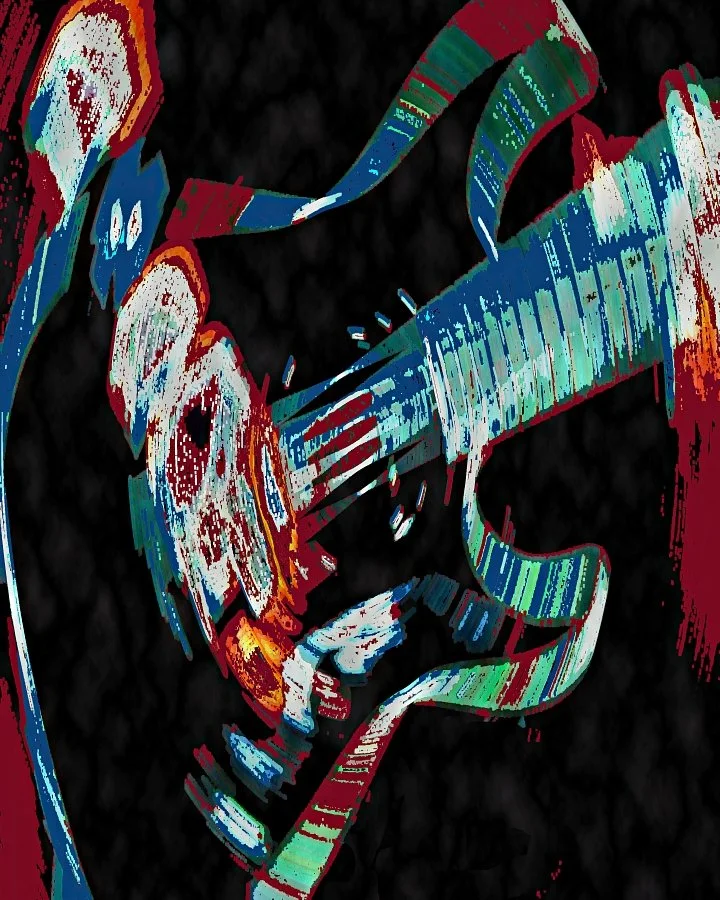

Guitar Zoom

Bottleneck

Slow Burn

Where my art began

(“This Is About the Guitar. And the People Who Can’t Put It Down.”)

The idea had to start somewhere.

Before there was a series, before there was a style, before there was abstraction, I was simply a photo enthusiast who loved music. I was a musician, a singer, a songwriter, a guitar player — and like many people who love music deeply, I wanted to be close to it. So I carried my big Nikon and heavy lenses into clubs and theaters, lugging them to local shows and national acts whenever I could.

Many of those national shows were blues-rock shows — not just because I loved the music, but because those were the rooms that would let you bring a camera inside. I shot countless performances, and I shared the images freely with local bands I followed and photographed often. That was part of the culture. Part of the exchange.

But somewhere along the way, I found my shot.

It wasn’t the wide stage.

It wasn’t the face.

It wasn’t the spotlight moment.

It was the extreme close-up of hands and guitar.

This shot was brutally difficult. You had to capture the exact moment — the right angle, the right timing, the right focus — while everything was moving. Hands flying. Strings vibrating. Lights flashing. Sweat. Motion. Noise. Out of hundreds of frames, maybe one would be special.

I took thousands of these photographs to build the collection I have today.

At this distance, it doesn’t matter if the musician is famous. The identity dissolves. What remains is the instrument and the human interaction with it. The guitar becomes the subject. The hands become the story.

The wear on the guitar.

The scratches and dents earned through use.

The rings and bracelets on the player.

The digging-in of fingertips.

The callouses.

The scars.

I often tried to catch the moment when the playing moved up the neck — when both hands could live inside the same frame. To do that, I usually had to be right at the front of the stage, close enough to see details that no one else could. Sometimes it was the blur of motion that made the image. Sometimes it was the impossible sharpness — the kind of sharpness camera companies used to brag about in watch advertisements.

Back then, cameras were compared by their ability to photograph a wristwatch in perfect focus — posed, lit, still.

I captured mine in flashing, strobing light — while everything was moving.

You could read the time on the watch.

You could see the hair on the back of a hand.

You could feel the tension in the strings.

I called these photographs Guitar Zoom.

They were made for guitar players — to decorate the spaces where they live, practice, and think. Because a guitar player is a guitar player all the time. It’s a shared identity. A massive, global group of people drawn to this instrument — from the most talented players to the absolute beginner.

Picking up a guitar is an act of curiosity.

Learning to make it sing is an act of patience.

Writing songs is an act of vulnerability.

Forming a band is harder than finding a spouse — because it’s more than two people learning how to become something together.

And then there’s the guitar itself.

The endless shapes.

The colors.

The wood grains.

The stains.

The fretboards made from dense, exotic woods gathered from around the world.

A guitar is beautiful when it’s perfect.

And it’s beautiful when it’s worn.

Like a well-used book, or a Bible that has been opened and studied thousands of times — the wear matters. The wear means something. Each guitar develops a personality. Some gain fame. Most simply gain history.

But eventually, I wanted more than the photograph.

I knew that thousands of concert photographers probably had images like these sitting quietly in their archives. I wanted to take this shot — this same framing, this same subject — and push it further. To move it from a great picture into enduring art. Something instantly recognizable as mine.

My style.

My voice.

My signature.

I wanted to capture energy.

Sound.

Transformation.

The movement from solid to sound.

From sight to memory.

From wave to particle.

From realism into abstraction — while always remaining the same shot: hands and guitar.

That pursuit has never stopped.

I love the guitar.

I love playing.

I love listening.

I love exploring pedals to create new sounds.

I love plugging into different amps to chase the elusive tone — the one that feels like recognition.

This work is for everyone who loves guitars.

For the players who spend countless hours practicing, only to realize the more they learn, the more there is to learn. For the beginner — even the toddler running tiny hands across the strings, startled by the sound they just created. The laugh. The smile. The moment of discovery.

It’s about the connection.

Sound leaves the hand, travels through space, enters another human being, becomes electrical signal, memory, emotion — and sometimes, meaning. Sometimes connection. Sometimes the simplest and most elusive thing we have.

This is where Guitar Zoom began.

And it’s still giving me more.

The chase of what can be removed.

What can be bent.

What can be recolored.

What can dissolve — while the essence remains.

My hope is that when you look at one of these pieces, you don’t just see it.

You hear it.

You feel the whole — and then you discover the tiny distortions, the details hiding inside the abstraction. The place where form becomes sound, and sound becomes memory.

This is Guitar Zoom.

This is where it all started.

And I’m still chasing it.

Where it all began

The idea had to start somewhere.

Before there was a series, before there was a style, before there was abstraction, I was simply a photo enthusiast who loved music. I was a musician, a singer, a songwriter, a guitar player — and like many people who love music deeply, I wanted to be close to it. So I carried my big Nikon and heavy lenses into clubs and theaters, lugging them to local shows and national acts whenever I could.

Many of those national shows were blues-rock shows — not just because I loved the music, but because those were the rooms that would let you bring a camera inside. I shot countless performances, and I shared the images freely with local bands I followed and photographed often. That was part of the culture. Part of the exchange.

But somewhere along the way, I found my shot.

It wasn’t the wide stage.

It wasn’t the face.

It wasn’t the spotlight moment.

It was the extreme close-up of hands and guitar.

This shot was brutally difficult. You had to capture the exact moment — the right angle, the right timing, the right focus — while everything was moving. Hands flying. Strings vibrating. Lights flashing. Sweat. Motion. Noise. Out of hundreds of frames, maybe one would be special.

I took thousands of these photographs to build the collection I have today.

At this distance, it doesn’t matter if the musician is famous. The identity dissolves. What remains is the instrument and the human interaction with it. The guitar becomes the subject. The hands become the story.

The wear on the guitar.

The scratches and dents earned through use.

The rings and bracelets on the player.

The digging-in of fingertips.

The callouses.

The scars.

I often tried to catch the moment when the playing moved up the neck — when both hands could live inside the same frame. To do that, I usually had to be right at the front of the stage, close enough to see details that no one else could. Sometimes it was the blur of motion that made the image. Sometimes it was the impossible sharpness — the kind of sharpness camera companies used to brag about in watch advertisements.

Back then, cameras were compared by their ability to photograph a wristwatch in perfect focus — posed, lit, still.

I captured mine in flashing, strobing light — while everything was moving.

You could read the time on the watch.

You could see the hair on the back of a hand.

You could feel the tension in the strings.

I called these photographs Guitar Zoom.

They were made for guitar players — to decorate the spaces where they live, practice, and think. Because a guitar player is a guitar player all the time. It’s a shared identity. A massive, global group of people drawn to this instrument — from the most talented players to the absolute beginner.

Picking up a guitar is an act of curiosity.

Learning to make it sing is an act of patience.

Writing songs is an act of vulnerability.

Forming a band is harder than finding a spouse — because it’s more than two people learning how to become something together.

And then there’s the guitar itself.

The endless shapes.

The colors.

The wood grains.

The stains.

The fretboards made from dense, exotic woods gathered from around the world.

A guitar is beautiful when it’s perfect.

And it’s beautiful when it’s worn.

Like a well-used book, or a Bible that has been opened and studied thousands of times — the wear matters. The wear means something. Each guitar develops a personality. Some gain fame. Most simply gain history.

But eventually, I wanted more than the photograph.

I knew that thousands of concert photographers probably had images like these sitting quietly in their archives. I wanted to take this shot — this same framing, this same subject — and push it further. To move it from a great picture into enduring art. Something instantly recognizable as mine.

My style.

My voice.

My signature.

I wanted to capture energy.

Sound.

Transformation.

The movement from solid to sound.

From sight to memory.

From wave to particle.

From realism into abstraction — while always remaining the same shot: hands and guitar.

That pursuit has never stopped.

I love the guitar.

I love playing.

I love listening.

I love exploring pedals to create new sounds.

I love plugging into different amps to chase the elusive tone — the one that feels like recognition.

This work is for everyone who loves guitars.

For the players who spend countless hours practicing, only to realize the more they learn, the more there is to learn. For the beginner — even the toddler running tiny hands across the strings, startled by the sound they just created. The laugh. The smile. The moment of discovery.

It’s about the connection.

Sound leaves the hand, travels through space, enters another human being, becomes electrical signal, memory, emotion — and sometimes, meaning. Sometimes connection. Sometimes the simplest and most elusive thing we have.

This is where Guitar Zoom began.

And it’s still giving me more.

The chase of what can be removed.

What can be bent.

What can be recolored.

What can dissolve — while the essence remains.

My hope is that when you look at one of these pieces, you don’t just see it.

You hear it.

You feel the whole — and then you discover the tiny distortions, the details hiding inside the abstraction. The place where form becomes sound, and sound becomes memory.

This is Guitar Zoom.

This is where it all started.

And I’m still chasing it.

The Ring Ignition

The Ring Ignition

This work begins with recognition.

At first glance, the guitar is unmistakable. The hands are present. The gesture reads immediately. The viewer knows where they are. That clarity is intentional—it allows entry without effort.

But the image does not reward a quick read.

With closer attention, the chain reveals itself. The strings on the fretboard are not static. They bend. They distort. They carry tension forward, not as illustration, but as evidence. The ignition does not begin in the burst of light—it begins at the string itself. The fretboard becomes the first fault line, the point where physical pressure starts its transformation.

The hands are real—but more than real at the same time. They are not symbolic, and they are not abstract. They carry weight, texture, and intention, yet they do not fully belong to a single moment. They appear slightly ahead of the body, pulled forward along the wave that precedes conversion into energy. They exist in a state that is hyper-present and displaced at once.

The guitarist seems present, but on inspection is largely absent—bent out of time, stretched by motion. Flesh, instrument, and force overlap without agreeing on where one ends and the next begins. What looks solid begins to slip. What feels familiar resists being fixed.

This ambiguity is not an effect. It is the subject.

The image lives in the moment where reality destabilizes just enough to reveal process. What is real and what is not cannot be resolved instantly. The viewer must look, re-look, and decide what they trust. The guitar remains legible, but everything around it is in flux—caught in transformation as physical motion becomes electrical current, passes through an amplifier, becomes sound, and finally resolves as a wave.

The ignition fills what was once empty space—not as background, not as atmosphere, but as consequence. Energy leaves the instrument. The system opens. The burst of red, orange, and yellow marks the instant vibration stops being contained and becomes transmission.

The outer ring holds. That boundary matters. The ignition does not explode outward; it remains contained, disciplined, controlled. Pressure becomes heat. Motion becomes signal. Conversion replaces collapse.

This is not an image of sound.

It is an image of transformation.

The guitar allows recognition.

The bending strings begin the chain.

The hands carry intention beyond the body.

What follows is conversion.

What happens next belongs to the viewer.

What Came Back

Studio Journal

What Came Back

I shared the work inside a Facebook group called Safe Space for Artists with no explanation and no framing beyond a simple invitation: What do you see?

The group did what artists do when they are given room instead of instruction. They responded honestly, personally, and without trying to resolve the image into a single meaning. What came back was not agreement, but alignment — many different visions orbiting the same gravity.

Some people saw an eagle playing a guitar. Others saw birds, ghosts, witches, or guides. Someone looked into what they described as a time tunnel. Another saw a ship floating on blood- and oil-slicked water. There were sunsets reflected on lakes, tree lines dissolving into abstraction, fire, water, light, and stillness. One person saw a sloth resting on a branch. Others didn’t describe what they saw at all — they described what they heard.

Slow. Heavy. Bluesy.

Smokey. Sultry. Intense. Soulful.

A guitar that burns.

A psychedelic guitar dream.

Fire breaking like a phoenix wave.

No one was asked to look for a guitar.

No one was asked to listen for music.

Yet music arrived anyway.

What mattered to me was not the imagery itself, but the way people entered the work through their own experience. Each response deepened the piece rather than closing it. The artwork became less like an object and more like a location — a place people could step into and leave something behind.

I didn’t write the responses. I didn’t guide them.

The only authorship I claim is the decision to leave the work open — and to offer a forum where interpretation was not corrected, ranked, or resolved.

After reading the comments, I had another idea: instead of summarizing them, I fed them directly into an AI system and asked it to do something unexpected — to write a song using the responses themselves as raw material. Not to explain the artwork, but to commemorate the moment of collective perception.

The result isn’t ownership. It’s evidence.

Evidence that meaning doesn’t live in a single mind.

Evidence that interpretation is a creative act.

Evidence that art can continue to evolve after it leaves the artist’s hands.

This feels like a new kind of collaboration — part human, part machine, part chance. An interactive, quantum-like process where meaning is shaped in the ether by whoever arrives, and then transformed again through another lens.

I may take the lyrics and ask Suno to turn them into an actual recording. Or I may not. Either way, the piece has already moved beyond its original form.

What follows isn’t an explanation.

It’s a trace.

One detail matters, and it’s easy to overlook because of the variety of responses: every person who responded recognized the presence of a guitar. Sometimes it appeared alone, sometimes embedded in fire, water, birds, or landscapes, sometimes secondary to another image — but it was always there. No one needed to be told what the object was. No one asked whether it was a guitar. Recognition happened immediately, and interpretation began after.

That distinction is important. The work did not fail into abstraction so far that reference disappeared. The guitar remained legible — not as a symbol to decode, but as a shared anchor. What diverged was not identification, but meaning. Each viewer carried the object somewhere different, using their own memory, emotion, and experience as the instrument.

This is the space I’m interested in: where recognition is stable, but perception is free.

Rocket 99

(lyrics generated from audience responses)

Verse 1

An eagle playing a guitar

That’s the first thing I saw

Somebody looking through a time tunnel

Something from before

A ship floating on blood and oil

Sun on water, stones

Everybody standing in the same place

Seeing it alone

Pre-Chorus

That’s what I love about art

That’s what I love about sound

Your life steps forward

And meets it now

Chorus

Sexy, slow, heavy, bluesy

Sultry, smoky, intense

Soulful fire in the strings

Burning where the light breaks in

Sexy, slow, heavy, bluesy

Let it roll, don’t stop

A guitar that burns

Rocket ninety-nine climbing up

Verse 2

I saw a scenic tree line

A sunset on a lake

Somebody saw a sloth just waiting

Like time could take a break

A guitar witch in the distance

Bird in a halo of flame

Everybody hears the same song

Just calling it a different name

Bridge

A ghost leading me

To the river of light

Phoenix wave breaking

In the middle of the night

Psychedelic guitar dream

Floating out of time

Fire and water shaking hands

Right on the line

Outro

I saw a really cool bird

You saw something from the past

That’s what love does with a sound

When you let it pass

Rocket ninety-nine…

Rocket ninety-nine…

Field Notes on Perception

Rocket 99.

The original photograph that Rocket 99 came from.

I shared the image without explanation and asked only one question: What do you see?

What came back wasn’t agreement — it was alignment.

Some people saw an eagle playing a guitar. Others saw a bird, a witch, a ghost, or a guide. One person looked into what they described as a time tunnel. Another saw a ship floating on blood- and oil-slicked water. There were sunsets, reflections on stone, tree lines, fire, and light. A sloth appeared, calmly watching from a branch.

Several people didn’t describe what they saw at all — they described what they heard.

Slow. Heavy. Bluesy.

Smokey. Sultry. Intense. Soulful.

A guitar that burns.

A psychedelic guitar dream.

Fire breaking like a phoenix wave.

No one was told to look for a guitar.

No one was told to listen for music.

Yet music kept arriving.

What interests me most is not the variety of images, but the consistency of feeling. Fire and water appear again and again. Movement through time. Passage. Thresholds. Reflection. Weight. Heat. Stillness before motion.

The image doesn’t behave like a picture. It behaves like a place.

People don’t examine it — they enter it. Their own history, memory, and temperament determine what steps forward to meet them. The work doesn’t explain itself. It doesn’t resolve. It waits.

One response said it best, without trying to:

That’s what I love about art. People’s experience shapes their interpretation.

That is the entire point.

I’m not interested in whether the viewer sees the same thing I do. I’m interested in whether the image gives them somewhere to arrive — and whether something inside them recognizes the sound when it gets there.

Torque

Rediscovered digital artwork from 2006 exploring force, rotation, and contact. Torque quietly previews ideas that would later become Without Square.

Torque

Torque

I found this piece on an old drive dated March 3, 2006.

This was the pre-iPhone world. Before social media feeds. Before filters, presets, algorithms, and named aesthetics. Before “glitch” became a style, before abstraction needed subcategories, before images were built for captions instead of contemplation.

At the time, I didn’t have the language for what I was doing. I only knew I was trying to hold onto a moment — not the guitar itself, but the force acting on it. Rotation. Resistance. The instant where motion stops being visual and starts becoming sound.

The image isn’t about distortion for its own sake. It’s about stress. Torque is force applied through rotation, but it only exists because something pushes back. Without resistance, there is no torque — only spin.

That tension is what remains legible here. The guitar never fully disappears, but it doesn’t resolve either. It stays caught between structure and release. The hand, the instrument, the strike — all present, all unstable.

The background matters more than I realized then. The black here isn’t pure. It’s clouded, textured, unsettled. It still carries atmosphere — a sense of space rather than absence. This differs from the pure black I would arrive at later, where the void becomes absolute and intentional. Here, the black still breathes. It hasn’t yet hardened into silence.

What feels most uncanny now is how closely this work previews what would later become Without Square — years before that language existed, before the decision to remove containment altogether became deliberate.

The image is already resisting enclosure. The guitar does not sit comfortably inside the frame. Motion pushes outward, blurs edges, refuses to settle. Even the background behaves less like a boundary and more like weather. The square is present, but it’s already being questioned.

In later work, the square would disappear entirely. The black would become absolute. Containment would be removed on purpose. Here, none of that had been decided yet — but the pressure against it is visible. The work is already testing how much structure it can dissolve without losing contact.

What’s unsettling is not that this looks like something I would make now. It’s that it feels like something that waited.

This file wasn’t curated or preserved intentionally. It wasn’t carried forward as part of a plan. It simply remained dormant until the surrounding work caught up to it — as if the ideas had to mature elsewhere before this piece could re-enter the conversation.

I don’t experience this as nostalgia. It feels more like recognition at a distance. A signal sent forward without knowing who would receive it — only to find that the receiver turned out to be the same person, years later, finally prepared to understand it.

This wasn’t chasing a trend. It came before most of them.

This wasn’t a beginning or an ending. It was a moment of alignment — captured before I knew why it mattered.

The name came later.

Torque

Because this work predates the term, it’s worth defining what glitch means here.

Glitch (in art)

In art, glitch refers to the intentional use of error, malfunction, or disruption—often drawn from digital systems—to create visual, sonic, or conceptual meaning.

Plain definition

A glitch is a breakdown in a system that becomes the work itself.

Instead of correcting the error, the artist preserves or amplifies it.

Where the term comes from

Originally an engineering term (mid-20th century) meaning a brief fault in an electrical or mechanical system

Adopted by artists once digital tools became common and errors became visible

In visual art

Glitch can include:

Pixel corruption

Compression artifacts

Data misalignment

Color channel separation

Frame tearing or repetition

Distorted edges caused by software or file misuse

Crucially: these effects are not decorative when used seriously—they expose the system underneath the image.

Conceptually, glitch art is about:

Revealing the hidden structure of technology

Interrupting smooth, consumable images

Questioning ideas of perfection, control, and realism

Letting process show instead of hiding it

A glitch says: this image is not natural — it is constructed.

Important distinction

Accidental glitch: a mistake

Artistic glitch: a chosen condition

Once the artist decides to keep it, it stops being an error and becomes material.

Why glitch mattered historically

Glitch art emerged as a recognizable movement in the early 2000s—alongside:

Early digital cameras

File compression

Internet image sharing

Software instability

It was a reaction against the promise that digital tools would make images cleaner, truer, and perfect.

Rocket 99

Rocket 99

This piece doesn’t sit still.

It moves before you finish looking at it — energy compressing, igniting, breaking loose. There’s no horizon line, no ground. Just thrust. Motion. Lift.

The form rockets upward and outward at the same time, angling like a jet in climb. That angle matters. It’s not drifting. It’s committing. Once the motion starts, there’s no returning to stillness.

The image pushes almost all the way to the right edge — 99% — and then stops. It doesn’t touch. That near-contact creates tension. If it reached the edge, the motion would resolve. Because it doesn’t, the motion continues beyond the frame, carried by the viewer instead. The eye keeps going. The energy stays alive.

Color burns hot against black space, not as decoration, but as velocity. The black isn’t emptiness — it’s resistance. Something to push against. Paper deepens this effect. The blacks feel heavier. The light feels denser. What looked like motion on a screen becomes force when printed.

The edges tear, smear, stretch. That isn’t accident or imperfection. Movement isn’t clean. Takeoff never is.

Hidden inside the abstraction is something familiar: the structure of a guitar, the gesture of a hand. Not illustrated. Not announced. They’re present as truth rather than subject. Some viewers will feel them before they see them. Some will see them suddenly, later. Some will never see them at all — and the piece still works.

That ambiguity is intentional. The image isn’t asking to be decoded. It’s asking to be experienced.

Rocket 99 lives in the split second where everything commits — when momentum outweighs gravity, when hesitation disappears, when staying still is no longer an option.

It isn’t about where it’s going.

It’s about leaving.

What is Real?

What Is Real? — Exploring Reality, Music, and Perception in Contemporary Digital Art

Is it what we touch?

Is it what we see?

Or is it what we don’t see—but feel—in our connection to the power of one that is the universe?

This piece began with that question and never tried to answer it.

At first glance, the image appears familiar: hands, a guitar, the moment of contact where sound is born. These are objects we recognize. Things we trust. Things we believe to be real because they exist in the physical world.

But the longer you look, the less certain that becomes.

The hands carry a kind of realism—but not a comfortable one. Their surface feels almost engineered, pushed just beyond the natural, sharpened into something intentional and slightly artificial. The guitar, by contrast, dissolves into abstraction. Its form remains, but its certainty does not. Light bends. Edges soften. The instrument becomes more suggestion than object.

Neither side fully claims truth.

This tension is deliberate. The work lives in the space between realism and abstraction, where certainty breaks down. Where what we see cannot be fully trusted, and what we feel begins to matter more than what can be verified.

The act of playing a guitar is not just physical. It is emotional, instinctive, and often invisible. The sound exists briefly, then disappears. The connection remains. That unseen exchange—the pressure of fingers, the vibration of strings, the resonance in the body—is as real as anything solid, even though it cannot be held.

This piece asks whether reality is defined by clarity, or by connection.

Is realism something we recognize with our eyes?

Or something we experience through tension, resonance, and presence?

There is no resolution here. No answer offered. Only a question held in balance.

What is real?

This work exists to sit inside that uncertainty—and to invite the viewer to sit there too.

What Is Real? (Extended)

I realized something today that quietly overturned one of my own assumptions.

I’ve been thinking about art as static — a physical object fixed in space. A print on a wall. A painting mounted and unmoving. Something that exists whether anyone is present or not.

But that isn’t actually true.

The moment art is seen, it stops being static.

What we experience is not the object itself, but light — waves reflecting off the surface of the work, traveling through space, entering the eye, converting into electrical signals, and finally being reconstructed inside the brain. The artwork does not arrive whole. It arrives as energy.

In that sense, visual art is no different from music.

Sound waves vibrate through air. Light waves reflect through space. Both require movement. Both require a receiver. Neither exists as experience without participation.

A painting hanging on a wall in a dark room is inert. Silent. Invisible.

Only when light touches it — and only when that light reaches a viewer — does the work come alive.

So what is real?

Is it the physical object — the paper, the pigment, the aluminum panel?

Or is it the wave event that occurs when light reflects and perception begins?

Music makes this obvious. Sound refuses containment. It escapes the instrument in uncontrolled waves, bouncing, penetrating, expanding outward, changing as it goes — like life itself. Even when recorded, it does not become still. When played back, it once again turns into vibration, breaking through walls, bodies, and space itself.

But visual art does the same thing — more quietly.

Light waves bounce. Reflect. Scatter. Shift with time of day, angle, distance, and the sensitivity of the eye receiving them. No two viewings are identical. No two minds reconstruct the same image in the same way.

The art object may remain unchanged.

The experience never does.

This collapses the idea of “static art.”

The work is not frozen. The work is a continuous event — a collaboration between material, light, and perception.

Which brings me back to the question that anchors this body of work:

What is real?

Is reality the object we can hold?

Or is it the invisible process that turns matter into experience?

This tension lives at the heart of Without Square.

The hands in this work are rendered with a heightened, almost artificial realism — pushed just beyond the natural. They feel solid, physical, present. The guitar, by contrast, dissolves into abstraction. Its edges slip. Its form refuses to settle. It behaves less like an object and more like a field.

Neither claims truth.

Both are unstable.

The hands appear real — but their realism is exaggerated, almost synthetic.

The guitar appears abstract — yet it is the source of sound, vibration, and wave.

What feels solid may be constructed.

What feels unstable may be closer to how reality actually behaves.

This is not an argument against physical art.

It is an argument against the idea that anything we experience is truly fixed.

Even a print on a wall becomes wave, energy, interpretation.

Even a song, once heard, becomes memory and meaning.

Everything passes through the same final stage:

the human nervous system.

Reality is not the object.

Reality is the encounter.

And Without Square is my way of staying inside that question — not resolving it, not framing it neatly, but letting it remain open.

Because the moment we decide something is fully contained, fully known, fully square —

we stop listening to how it actually moves.

Addendum: Particle or Wave

This question keeps widening.

In quantum physics, the most unsettling discovery was not that light behaves like a wave, or that matter behaves like a particle — but that neither description is complete on its own. What something is depends on how it is encountered.

Unobserved, it spreads. Interferes. Exists as probability.

Observed, it collapses. Localizes. Becomes a thing.

So the question was never simply particle or wave.

The question was always: under what conditions does it become one or the other?

That same tension exists here.

An artwork, unencountered, is dormant.

Encountered, it becomes event.

A human body appears particle-like — bounded, measurable, located in space.

But experience is wave-like — emotion, memory, influence, resonance — extending beyond the body, changing others, lingering after presence is gone.

We are solid and diffuse at the same time.

Discrete and continuous.

Observed and observing.

Which brings the question to a place I didn’t expect when I began this work.

The question is no longer What is real?

The question becomes:

Are we particles, or are we waves?

And if the answer is both —The question becomes:

Are we real?

Not as objects.

Not as fixed identities.

But as encounters — changing through observation, collapsing into form only when touched by another consciousness.

Reality may not be what exists.

Reality may be what happens.

And Without Square is my way of staying inside that uncertainty —

not to resolve it, but to remain honest about how unstable, participatory, and unfinished experience actually is.

The Ring

Submitting Chasing the Setting Sound (Float) and Melt 5

Melt 5

Chasing the Setting Sound (Float)

Lake Effect: Artists from Cleveland Now

I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about what it means to submit work to an institution—not just whether the work is “good enough,” but whether it is honest enough about where it comes from and where it’s going.

For the Cleveland Museum of Art’s Lake Effect: Artists from Cleveland Now, I chose to submit two works: Chasing the Setting Sound (Float) and Melt 5. They are not meant to summarize everything I make. Instead, they mark a through-line—a point of origin and a point of pressure—within the body of work I’ve been developing under the framework I call Without Square.

Chasing the Setting Sound (Float) is where that framework began. The piece originated from a practical problem rather than a theoretical one. I was thinking about how an image might exist on black without being boxed in by a printed square—how to let a form sit directly in space without containment. Removing the square wasn’t a stylistic move at first; it was a refusal. Once the frame disappeared, the image stopped needing to resolve itself. Edges softened. The guitar ceased behaving like an object and began to act more like a presence—floating, provisional, unfinished. That decision became foundational.

The title comes from music. Anyone who plays knows the feeling of chasing a sound that never quite settles. Visually, that idea carries through the work. The image resists grounding. It hovers between recognition and abstraction, between contact and release. What remains is not an instrument, but the sensation of sound just before it becomes fixed.

Melt 5 pushes that idea further. Where the earlier work floats through suspension, Float 5 floats through instability. It originates from the same photographic language, but the form is no longer allowed to hover gently. Instead, it is stretched, torqued, and compressed by opposing forces. There is no central anchor and no resolved edge. The image behaves like a field under stress—directional, charged, unresolved.

Together, these two works outline what Without Square has become for me. It is not just the absence of a frame. It’s a way of working that challenges visual enclosure at multiple levels: compositionally, materially, and conceptually. Cropping avoids symmetry. Space refuses to sit behind the subject. Even when the work exists within a rectangular format, it resists behaving like a contained object.

Submitting these pieces to Lake Effect feels appropriate not because they reference Cleveland directly, but because they come out of a Cleveland way of thinking—working with constraint, weather, friction, and persistence. This exhibition consciously recalls the spirit of the Cleveland Museum of Art’s historic May Show, a tradition that centered regional artists and the conditions they work within. Lake Effect isn’t about nostalgia; it’s about present tense. These works live firmly in that present.

Whether or not they are selected, the act of submitting them together matters. They represent a clear decision about what I’m producing now, what I’m refusing, and what I’m allowing to remain unresolved. The square is gone. What’s left is movement, pressure, and the space where something almost settles—but doesn’t.

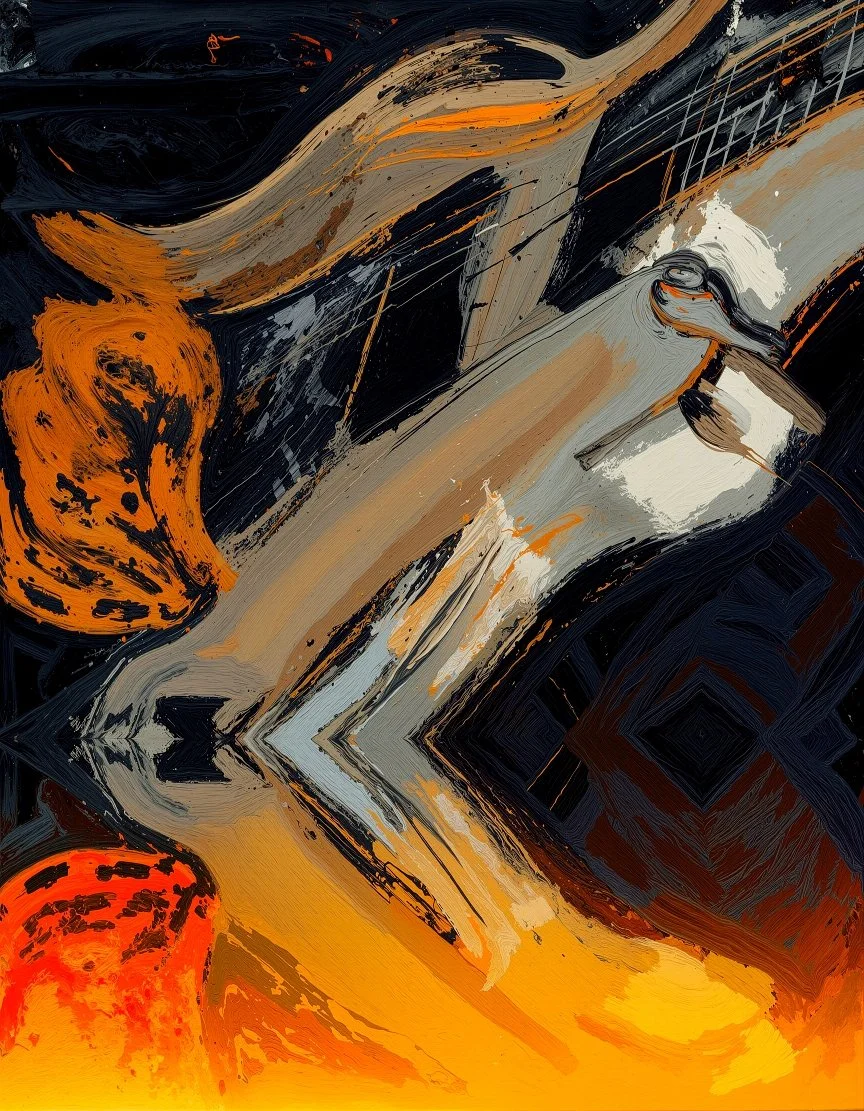

Melt Drift

Melt Drift

Without Square is not just about removing borders.

It’s about removing containment.

In Melt Drift, there is no evidence of a frame having ever existed. The form does not appear cropped, broken, or escaped. It appears naturally unresolved—as if it never agreed to become rectangular in the first place.

This is important:

The work does not rebel against structure.

It simply ignores it.

Form and suspension

Melt Drift exists in a state of held motion.

The shape suggests gravity, heat, and flow—but nothing completes. There is no downward collapse, no directional finish. Instead, the piece hovers in a condition where movement has slowed just enough to be observed.

This is where “drift” matters.

Drift is not chaos.

Drift is motion without urgency.

The form bends and softens, but it does not fall apart. It carries weight without heaviness. The edges dissolve, yet the interior remains coherent. That balance is difficult—and it’s achieved here.

Color as temperature, not symbolism

The palette reads as thermal, not emotional.

Warm ochres and ambers coexist with blacks and grays, but none dominate. The warmth does not glow outward; it stays contained within the form, like residual heat. This reinforces the sense that the object is cooling, not igniting.

Nothing here is dramatic.

Nothing is illustrative.

The colors behave like materials responding to pressure rather than signals asking to be interpreted.

Rock Star 12 — Out of Plane

Here, the frame doesn’t simply loosen — it fails.

Rather than extending outward evenly, the image begins to skew, warp, and collapse along its own surface. The picture plane bends. The bottom edge gives way. The sense of “ground” disappears. What remains is not depth in a traditional sense, but dimensional instability — a feeling that the image no longer occupies a single, reliable plane.

This is not 3D, and it is not perspective. There is no vanishing point, no illusion of space receding neatly into the distance. Instead, the space itself appears under stress, as if the image were caught mid-transition between states. The guitar and figure remain legible, but the environment around them becomes volatile — pulled inward in some areas, swollen outward in others.

Liquify tools were used intentionally, not to distort the subject, but to deform the space around it. Subtle applications of “sucker” and “bloat” introduce pressure and curvature, creating a warped field where motion behaves inconsistently. The result is a sense of being slightly out of alignment — as if the image has slipped out of its assigned dimension.

The black surrounding the image is no longer passive background. It presses inward. It behaves like mass. It interrupts, intrudes, and destabilizes the composition rather than framing it. The image doesn’t sit inside the void — it is being eroded by it.

In this way, Out of Plane extends the ideas behind Without Square rather than repeating them. Where earlier works rejected containment, this piece questions the stability of the container itself. The square is no longer something to escape — it’s something that can no longer hold.

Sound has always been central to this work. A guitar is not just an object here; it’s a source of vibration — a frequency strong enough to bend structure. The image behaves the way loud sound feels: not directional, not polite, and not confined to the space it’s supposed to occupy.

Rock Star 12 — Out of Plane exists between moments. Between surfaces. Between dimensions. It is less an image of a performance than a record of pressure — what happens when motion, sound, and energy exceed the limits of the plane meant to contain them.

Jonny 5 without time

Jonny 5 Out of Time

Jonny 5 — Out of Time

There is something unsettling about this image, and it took me time to understand why.

When I look at Jonny 5 — Out of Time, I can’t hold the entire face at once. If I lock onto one version of the face, the other disappears. When my eye shifts, the first collapses. I can’t see both simultaneously. The image refuses to resolve.

This isn’t an accident.

The faces are not just doubled in space—they are separated by color. One resolves through red, the other through green. The human eye treats these colors as opposites. When one becomes dominant, the other is suppressed. Perception turns into a switch rather than a blend.

The result is a kind of visual instability. The image doesn’t exist all at once. It exists over time. You don’t see it in a single moment—you move through it.

That experience mirrors what the piece is about.

This isn’t a portrait of a musician frozen in performance. It’s an image of sound outrunning the body that produced it. Identity fragments. Time slips. The figure exists in more than one state but cannot be perceived as whole. What you see depends on where you place your attention.

In that sense, Jonny 5 — Out of Time pushes Out-of-Square beyond form and into perception itself. The square isn’t just abandoned physically—it’s abandoned cognitively. The image refuses a single, stable reading. It demands participation. It requires the viewer to accept incompleteness.

The instability isn’t something to solve. It’s the subject.

If the image feels unresolved, that’s because it is. It exists in transition—like sound, like memory, like vibration. You’re not meant to see everything at once.

You’re meant to move.

And if that feels uncomfortable, it may be because the mind wants edges, certainty, and completion.

This piece offers none of that.

It may only fully make sense

if your mind is not square.

The Firerocks Series

Original Photoshopped Firerocks picture from 30 years ago

Adapting Firerock to Without Square

To show the progression from then to now, I include this image from my Fireworks series—created roughly thirty years ago—where I combined live musical performance with layered fireworks imagery using early Photoshop techniques. At the time, I didn’t have the language, the tools, or the resolution to fully realize what I was reaching for. I was cutting, isolating, recombining—removing bodies, breaking forms, letting energy exist without its original container.

Looking at it now, this work reveals itself as an early instinct toward what would later become Without Square. The image wasn’t framed in the traditional sense. It was assembled through subtraction and displacement. The subject was already escaping its original boundaries, even if the final result still carried the weight of the square it lived inside.

This wasn’t a finished idea. It was a signal.

What’s changed isn’t the intent—it’s the precision. Today, the tools allow the concept to complete itself. The square no longer needs to be disguised or worked around. It can be acknowledged, stripped of authority, or removed entirely. What began as experimentation has become a deliberate system.

In that sense, Without Square didn’t appear suddenly.

It was forming long before it had a name.

Out-of-Square: The Outer Square Paradox

At the center of Out-of-Square is a simple refusal:

the image does not accept the square as an authority.

The work speaks about floating—about form existing without corners, without containment, without inherited rules about where an image must stop. The subject softens into space. Edges dissolve. The picture behaves as if the square never existed.

And yet, in some pieces, it unmistakably does.

This is where Outer Square appears.

Out-of-Square is the concept—the intent to move beyond the square as a governing structure. Outer Square is a specific condition inside that concept: a deliberate contradiction where the square remains visible, but no longer functions as a container.

Every Outer Square is still a square.

But the image does not live inside it.

Instead, the picture presses outward. It leans against the boundary, breaks the agreement, and visually exits the shape. The square becomes a reference plane rather than a frame—something the image acknowledges, then ignores.

When you look at an Outer Square piece, your eye doesn’t register “framed artwork.” It registers escape. The square becomes residue. A trace of structure. A reminder of how images used to behave.

This tension is intentional.

We are conditioned to trust the square. It has always been the quiet contract between artist and viewer: this is where the image ends. In Outer Square, that contract is quietly broken. The image doesn’t destroy the square. It simply refuses to obey it.

That distinction matters.

The square is not rejected outright—it is stripped of authority.

This is what gives Outer Square its irony. The work claims a no-corner space while allowing the square to remain present. Not as a ruler, but as a foil. The image exists out-of-square while the square itself lingers as an outer reference.

So yes—there are corners.

They’re just no longer in charge.

The work lives in that moment where structure still exists, but meaning has already moved beyond it. Where the image remembers where it came from, even as it insists on becoming something else.

That is the paradox of Outer Square within Out-of-Square:

The square remains—but the picture doesn’t stay.

And once you see it that way, the square never looks the same again.

And then there’s the last, quiet layer of irony.

After all of this—after rejecting corners, after pushing images out of frames, after loosening the authority of the square—the work is presented inside a space literally called Squarespace.

A square space.

It’s not a joke, but it’s not accidental either.

The platform is structured. Gridded. Predictable. It’s built on alignment, margins, and containment. And yet, within that environment, the images refuse to behave. They don’t sit politely. They don’t center themselves for comfort. They push outward, visually and conceptually, against the very system holding them.

This matters.

Because Out-of-Square isn’t about escaping structure altogether. It’s about revealing it—and then moving beyond it. The square still exists. The system still exists. The rules are still visible.

They just aren’t in control.

So the work lives out-of-square, inside Square Space, while asserting a no-corner space of its own. The contradiction isn’t resolved. It’s preserved. Held in tension.

The image doesn’t deny the square.

It simply refuses to stay inside it.

And that’s where the work actually begins.

Out-of-Square is not about showing less detail.

It is about removing so much that the image can no longer complete itself on the surface.

The instrument is largely absent.

The body that once defined it is gone. What remains are functional remnants—surfaces of contact, traces of use—freed from the objects that once contained them. A part is no longer a part. It becomes a shape. A location. A record of motion.

Figures are not rendered in full. They are reduced to fragments. Not anatomical descriptions. Not photographic accuracy. Only the minimum required to suggest action.

This is not a close-up that breaks past the edge of a frame.

This is not an image asserting itself through excess.

It is built through subtraction.

So much is removed that what remains cannot stand alone. The viewer is required to supply what is missing—the instrument, the gesture, the pressure, the sound. The work does not finish itself.

In Out-of-Square, absence is not empty space. It is an active component. Removal becomes the organizing structure. Meaning forms where detail has been deliberately withheld.

If the viewer looks only for what is present, the image will feel incomplete.

If the viewer expects resolution on the surface, it won’t arrive.

The work resolves only through participation—through imagining beyond what is shown rather than staying confined to what is given.

And if nothing appears to resolve at all, that may say less about the image

and more about the shape the mind prefers to remain inside.

The work resolves only through participation—through imagining beyond what is shown rather than staying confined to what is given.

If the image feels unfinished, that is intentional.

If it feels incomplete, that is the invitation.

You may only understand Out-of-Square

if your mind is not square.

Blue Hands 5

This piece began with a guitar, but it didn’t stay there for long.

What remains recognizable is not the instrument itself, but the place where touch happens. The pickguard — a surface designed to receive motion — becomes the anchor. Everything else is allowed to soften.

The hands are no longer literal. They are not meant to be studied or identified. They exist in motion, dissolving into color and air, somewhere between action and sound. What matters is not the hand, but the act of contact — the moment just before vibration becomes music.

Blue dominates the image intentionally. Not as mood, and not as symbolism, but as temperature. Blue slows the eye. It removes urgency. It allows the viewer to stay rather than search.

The sky is not a background. It is part of the form. There is no edge separating subject from space. The image does not sit inside a square or press against boundaries. It floats, uncontained, the way sound does.

This work is meant to be calming — not decorative calm, but suspended calm. A place where nothing is demanded of the viewer. No story must be solved. No emotion must be named. You can simply remain with it.

Blue Hands 5 is part of an ongoing exploration of work created without square edges — images that resist confinement and allow form to dissolve naturally into space.

Sometimes the most honest moment in music is not the note itself,

but the touch that brings it into being.

Title: Lighter 9 — The Note Without Edges

Lighter 9

There is a moment before sound exists.

Before a note is struck. Before a voice opens. Before intention becomes vibration. It is the instant where possibility gathers inside the hand.

Lighter 9 lives inside that moment.

What appears to be a lighter is not simply an object—it is a slide. On a guitar, a slide removes the boundaries between notes. There are no frets. No fixed positions. Pitch becomes continuous, fluid, infinite. You are no longer choosing a note—you are traveling through sound.

That matters.

This image is not about flame. It is about unbounded pitch. About sound without steps. About movement between notes instead of arrival at them. The slide allows the guitarist to pass through frequencies that are not normally accessible, creating tones that exist between the expected and the unknown.

That is the true subject of this piece.

The hand is real.

The guitar is real.

The slide is real.

But the edges are not fixed.

Using what I’ve been developing as my micro-edge, the form dissolves almost imperceptibly into the surrounding black. Nothing is cropped. Nothing is framed. The subject is not contained. It emerges, transitions, and releases into space—just as the slide releases sound from rigid structure.

This is what I call referential abstraction: the physical world remains recognizable, but its boundaries soften. The object is still there, yet its meaning is no longer limited to what it is. It becomes what it does.

The orange micro-burst at the wrist is not decoration. It is not “sparkle.” It represents energy leaving the body—the moment of transformation. Not fire from the slide, but motion through sound itself. The slide does not create tone. It reveals it.

And the black surrounding the form is not background. It is silence. It is the unplayed frequency. It is the space where sound has not yet entered.

This work exists within my ongoing exploration of “without square”—art that refuses containment, refuses geometry, refuses edges that say where something must stop. Just as the slide has no fixed pitch, the image has no fixed boundary. It does not sit inside a frame. It breathes into the void.

In Lighter 6, the guitar is present but not dominant. The slide is visible but not the focus. The true subject is continuity—the smooth, unbroken movement between states. Between silence and sound. Between one note and the next. Between what is defined and what is still becoming.

This is not an image of performance.

It is an image of possibility.

A note without edges.

A sound without borders.

A moment where art is no longer fixed—but free.

Fractured Float 4

A first work after the manifesto. A statement of what comes next.

There are moments in an artist’s life when a piece arrives not as an experiment, but as a recognition. Not as a variation, but as a confirmation. Fractured Float 4 is that moment for me. It is the first work completed after articulating my manifesto—my commitment to referential abstraction, to Without Square, and to a language that refuses containment while remaining anchored to a real object.

This piece is not simply an image. It is an event in which form, energy, and perception meet. What follows is an extended articulation of what Fractured Float 4 is, what it is doing, and why it matters within the larger arc of my work.

From Object to Event

At its core, the work still contains a guitar. The referent is not erased; it is honored. But it is no longer illustrated. The guitar is no longer presented as a thing to be looked at. It has become something to be experienced.

This is the defining principle of referential abstraction: the object remains present, but meaning is carried by transformation rather than depiction. The guitar does not disappear—it evolves. It becomes vibration, memory, resonance, fracture. The image does not represent the guitar; it behaves like it.

In Fractured Float 4, the instrument is liberated from geometry. There is no frame, no rectangular boundary, no architectural containment. It is form without enclosure—a presence that exists without edges, floating in a void that is not emptiness but possibility.

Without Square: Form Without Boundary

Much of art history is defined by containment: canvas edges, frames, borders, and architectural limits. Without Square is my refusal of that inherited geometry.

Here, the form is not cropped to fit a rectangle. It is not subordinated to the logic of the wall or the screen. Instead, it occupies space on its own terms—organic, asymmetrical, and unconfined. The piece does not sit inside a shape; it is the shape.

This is not merely aesthetic. It is philosophical. The work asserts that meaning does not require containment, that presence does not require a box, and that an object can exist fully without being enclosed.

Fracture as Energy, Not Decoration

The internal distortion of the form is not a stylistic effect. It is not a filter applied for visual novelty. The fracture reads as force: vibration, pressure, memory bending, time pulling the image apart. It behaves less like surface ornament and more like an energetic field.

This is where the work crosses from image into process. What you see is not just what the guitar looks like—it is what the guitar does. Sound becomes visible. Motion becomes form. Resonance becomes structure.

The fracture is not destruction. It is transformation.

Color as Structural Force

The dominant reds, oranges, and golds are not simply chromatic choices. They are doing conceptual work. They carry heat, compression, ignition. Color becomes architecture.

Rather than decorating the form, color becomes the mechanism through which the form is understood. It is not added; it is intrinsic. This is not “color on an object,” but color as the object’s internal logic.

In this sense, Fractured Float 4 treats color as time, as pressure, as force. It is not describing energy—it is energy.

Micro-Life: The Presence of the Small

One of the most important aspects of the piece is almost invisible at first glance: tiny two-pixel artifacts embedded within the form. These minute details act like grain in film, fiber in paint, or surface noise in vinyl. They introduce biology into the digital.

They give the piece animal life.

Perfection would have sterilized the image. Instead, these micro-elements make it breathe. They introduce irregularity, vulnerability, and presence. The work feels alive not because it moves, but because it is imperfect in the way living things are imperfect.

Flow and Solidity: A Quantum Object

One of the most striking qualities of Fractured Float 4 is its dual nature. It feels simultaneously fluid and solid. It occupies space while resisting containment. It appears stable while suggesting motion.

In this way, the piece behaves almost quantum-like: wave and particle, motion and stillness, identity and dissolution coexisting in a single visual field. The guitar is there—but so is the event of it becoming something else.

This is the visual language I have been searching for: an object that is both itself and the process of transformation.

The Giving Image

I describe this piece as “giving” because it does not exhaust itself. It rewards sustained looking. There is always another micro-event to discover, another path for the eye to travel. The work does not present a single conclusion; it offers a field of attention.

This is the difference between decoration and art.

Design satisfies quickly. Art continues to reveal.

Position Within the Body of Work

Fractured Float 4 is not a variation. It is a threshold.

It stands as the first work created after my manifesto, and it functions as a declaration of intent:

The guitar remains the referent.

Geometry no longer contains the form.

Color becomes structure.

Fracture becomes energy.

Presence replaces representation.

Without Square — Defining the Architecture of My Work

After nine pieces and nine reflections, something has become clear to me.

What I have been making is not a series of images.

It is a system.

I have been circling one idea again and again—sometimes quietly, sometimes forcefully, sometimes intuitively—but always with the same underlying condition:

Without Square.

This is not a style.

It is not an effect.

It is the architecture of how my work exists.

What “Without Square” Means

The square is the default container of images. It tells us where a work begins and where it must end. It feels neutral, but it is not. It imposes order before meaning. It decides space before the image has earned it.

In my work, that geometry is removed.

Without Square means the form is not governed by a frame.

It is governed by presence.

The image is not placed into space.

It must justify its existence within it.

Black is not background.

Black is structure.

It is the void that defines what is allowed to remain.

Two Forces Within the Same System

Everything you’ve seen in the last nine pieces operates under this same condition—but with different emotional physics.

In Chasing the Setting Sound (Float), the form emerges.

The energy is continuous.

The edges are quiet.

The image does not challenge the space—it inhabits it.

The void remains dominant.

The form exists by permission.

In Rockstar 7: Bam!, the relationship shifts.

Here, the energy is compressed.

Color does not drift—it strikes.

The form presses outward, testing how much presence it can claim without breaking the discipline of black.

This is no longer emergence.

This is impact.

Yet both pieces obey the same rule:

The black is not decorative.

The square is not in control.

The form must earn its place.

Different forces.

Same architecture.

Why This Is Not Abstraction for Its Own Sake

My work is always anchored to something real: a guitar, a musician, a gesture, a moment of sound. I do not erase the object—I distill it. What remains is not representation, but energy, motion, and structure.

This is what I call referential abstraction.

The image does not illustrate the object.

It reveals what the object is doing in space.

Without Square is how that revelation is made possible.

What This Changes Going Forward

I am no longer experimenting with this language.

I am working inside it.

Every piece now asks the same question:

Does this form deserve to exist within the void?

If it does not, it is removed.

If it does, it remains—uncontained by edges, unsupported by decoration, defined only by presence.

This is not about making louder images.

It is about constructing visual objects that can survive silence.

The Work Is No Longer About the Frame

The square is gone.

The background is no longer passive.

The image is no longer protected by geometry.

What remains is the work itself—

and the black that allows it to speak.

This is not a phase.

It is the structure of what I am building.

Without Square.